READ CHAPTER 1

GALLERY

WHO'S WHO

ATLAS

MYTHS DEBUNKED

FAMILY TREE

CONTACT THE AUTHOR

UPCOMING EVENTS

REVIEWS

CHICAGO HISTORY LINKS

READING SUGGESTIONS

BUY THIS BOOK

Chicago's Bank Panic of 1896

It seemed that the National Bank of Illinois, which had withstood all of the city’s previous panics, had invested $2.4 million in the unprofitable Calumet Electric Street Railroad, including a $900,000 payment that was hidden in a foreign-exchange account. Over the weekend, examiners had discovered the bank didn’t have enough money to cover all of the loans it had been making. It was the largest bank failure in the country’s history up until that time. Other Chicago banks that had relied on the National Bank for financing closed their doors as well.

Wasmandorf played with his eight-year-old granddaughter for almost an hour. Then he said he was tired, raised her in his arms, and kissed her upon the lips. Saying nothing to his wife, he went upstairs and into a little bedroom, where almost nothing had been touched since his grown son, Richard, died in the room of pneumonia four years earlier.

Wasmandorf carried a revolver that had belonged to his son. He stretched himself across the bed, in which no one had slept since Richard died. He put the muzzle to his right temple and pulled the trigger. Downstairs, his wife heard the sound but thought it was an article of furniture falling to the floor. She sent a servant upstairs to investigate. A minute later, the servant rushed back down, speechless.

The banker who was reported to be at the source of all the trouble — William Hammond at the National Bank of Illinois — went about his business as if nothing were amiss. He came down to the bank for an hour each morning, then came back for another hour in the afternoon, had dinner at the Union League and returned home to Evanston.

"He always acted as if nothing had happened," said Ryan, the old bank policeman, "and was just the same to all of us as before the bank failed. When he was in here on Thursday, says I to him, ‘You look very well, Mr. Hammond,’ and says he to me, ‘I’m feeling pretty good.’ He was not one of the kind of men who kill themselves. He was too big and solid, too much bone and sinew. Ever since the bank failed, says I to myself, ‘Hammond won’t kill himself; he is too big.’ Not once did I see any sign that he was taking his trouble to heart, and I have heard him say he did not care for what the newspapers said about him."

On Saturday, January 2, 1897, Hammond’s wife awoke at 6 o’clock and noticed that the door connecting her bed chamber to his was ajar. She went into his room and saw that his night robe was hanging over the rear of the bed. His gold watch had been wound and hung on the arm of the chair near his bed, where he always put it before going to sleep. His vest, a grayish tweed, was on the same chair, but his trousers, coat and underclothing were nowhere to be found. Neither was he.

On a hunch, they went to a nearby pier and found some scraps of paper. The rain during the night had soaked the papers, which had clung to the boards. The rain had also washed away most of the ink on the papers, but the men recognized Hammond’s handwriting and his signature. He had apparently torn the paper into shreds before throwing it away.

The neighbors found footsteps in the wet sand, indicating that Hammond apparently had paced up and down the beach before going out on the long reach of black timbers. The rain and the fog made the pier wet and slippery, and the dim light would have made it difficult for Hammond to reach the end of the dock, a thousand feet from shore.

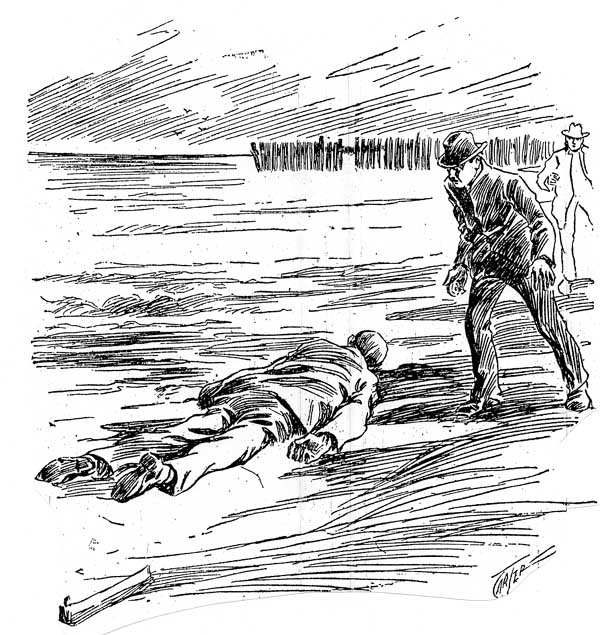

Tugboats searched the waters for his body, but their grappling hooks found nothing. A couple of boys found Hammond that afternoon, at the water’s edge a half-mile from the pier, dressed in underclothes, a dark bathrobe and felt-lined shoes. When the police arrived, the body lay face-down, half-buried in the sand, the waves washing over it. The body was somewhat discolored, and looked as if it had been in water much longer than it really had. A memorandum in one of the bathrobe’s pocket listed his bank’s assets and outstanding loans.

Even before that infamous bombing, one of the anarchists later charged in the case had accused Dreyer of corruption. Then, Dreyer was on the grand jury that indicted the seven anarchists of bombing the police at Haymarket. Finally, he became one of the most passionate advocates for mercy toward the anarchists, breaking down in tears as he stood in Governor John Altgeld’s office, watching him sign the pardon. Dreyer carried that pardon order from Springfield to the anarchists at the Joliet prison in June 1893, around the same time that E.S. Dreyer and Company began running into trouble.

While the Panic of 1893 forced other banks to close, Dreyer managed to hold off failure by taking out loans from his friends at the National Bank. More loans were always needed, and National Bank willingly obliged, until Dreyer had piled up $500,000 in debt to the bank. Dreyer also developed a habit of "borrowing" money from one of the city’s park districts, for which he served as treasurer, when his firm’s accounts were running low.

Now he lay in bed day after day, expecting criminal charges and suffering from a malady the newspapers never bothered to diagnose. After going to Dreyer’s house, where police officers guarded the entrances, one of the banker’s acquaintances recounted the visit: "I found him suffering the most intense pain. His physician was present and enjoined me not to worry him with too many questions. The banker was undoubtedly glad to see me and began talking at once on the business which most interested me.

"‘My friend,’ said he, ‘you can’t imagine how gladly I would leave this sick-bed, but my ailment is of such a type that I am compelled by my good doctor here to keep cooped up. I am most desirous of getting out to business again... I want to say to you and to all my friends that there are enough assets to pay every claim against the estate and something will be left for me to start over.’

" ‘Mr. Dreyer,’ I said, ‘you will do nothing rash?’

" ‘My dear friend,’ he replied, ‘I will not. I have inclination to. I will never commit suicide.’ "

Another associate said Dreyer’s "paroxysms of pain were becoming less frequent and less painful," but a newspaper reported that Dreyer was "helpless from old complications, which have been greatly aggravated by his mental worry."

Four months later, Dreyer was indicted on fifteen charges, including obtaining money under false pretenses, conspiracy and larceny. The grand jury commented: "The investigation of the affairs of E.S. Dreyer and Company has revealed a condition at once criminal and shocking."

He was found guilty again on March 1, 1900, and when all of his efforts to appeal had failed, he was sent from Cook County Jail to the Illinois State Penitentiary in Joliet on December 31, 1902, riding the same train line Luetgert had taken four years earlier.

As he left for Joliet, Dreyer turned up the collar of his ulster overcoat to shield his face from the cold. He wore an old-style black derby over his short gray hair and clutched a cigar nervously in his prominent white teeth. "I am going to the penitentiary an innocent man," Dreyer told bailiff Thime. "This talk that I have something to expose when I am free is all rot. I shall do no talking, but somebody else, a friend of mine, may."…

A "trusty" convict, C.V. Kelly, greeted him at the prison gate in Joliet.

"I am glad to see you, Kelly," said Dreyer, shaking his hand.

"But I am not glad to see you here," Kelly promptly answered.

After he had entered the prison, Dreyer glanced into an office and saw Charles W. Spalding, another banker who had been convicted in the scandals of 1896 and 1897. Spalding was hard at work, managing the penitentiary records, and he didn't notice Dreyer.

Dreyer was paroled in 1905, and he died from heart disease on June 22, 1918.

© 2003 by Robert Loerzel.

Pictures: Banks, Chicago Tribune, Dec. 22,

1896; Hammond's body on beach, Chicago

Tribune, Jan. 3, 1897; Dreyer, Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1897; Dreyer

goes to prison, Chicago Daily News, Dec. 31, 1902.

SOURCES

Otto Wasmandorf's suicide: Chicago Tribune, Dec. 28, 1896.

Ryan's comments on Hammond: Chicago Tribune, Jan. 3, 1897.

Willard's comments: Chicago Tribune, Jan. 3, 1897.

Hammond's suicide: Chicago Tribune, Jan. 3, 1897; Chicago Daily News, Jan. 2,

1897, later edition; Chicago Tribune, Jan. 3, 1897; Chicago Tribune, Jan. 3,

1897.

Comments from Dreyer's acquaintances: Chicago Daily News, Jan. 3, 1897.

"helpless from old complications": Chicago Tribune, Jan. 4, 1897.

Dreyer's indictment: Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1897.

Dreyer's convictions and appeals: Clerk of the Circuit Court of Cook County,

archives.

Dreyer sent to Joliet: Chicago Daily News, Dec. 31, 1902.

Dreyer dies: Chicago Tribune, June 22, 1918.