READ CHAPTER 1

GALLERY

WHO'S WHO

ATLAS

MYTHS DEBUNKED

FAMILY TREE

CONTACT THE AUTHOR

UPCOMING EVENTS

REVIEWS

CHICAGO HISTORY LINKS

READING SUGGESTIONS

BUY THIS BOOK

The Murder Case of George Painter

George H. Painter gets just one offhand mention in Alchemy of Bones, but it is a prominently placed mention, right there in the first paragraph of Chapter 1.

I was nearly done with the research and writing of Alchemy of Bones before I looked into Painter's story and discovered how fascinating it was. It really has little to do with the story of Adolph Luetgert, but it is nevertheless and interesting example of another Chicago murder trial in the 1890s. The Chicago Daily News called it "one of the most atrocious murders in the annals of Chicago's history." And the case ended with a hanging that surely ranks as one of the most brutal executions in the city's history.

Newspapers described Painter as a handsome, well-dressed young man, a bit of a dandy, who spoke as if he were well-educated. The son of a Methodist clergyman, Painter was thirty-six and he had lived in Chicago for fifteen years, on and off.

A woman named Mrs. Truesdale — one of four people who lived on the second floor — was still under the impression that Painter and Martin were married when she spoke with a Daily News reporter. "She (Martin) often told me that ... her husband got into some kind of trouble there and his parents repudiated him," Truesdale said. "His father is a preacher, she said, and she was the only one who stuck to the young man in his trouble. They had been all over the country, but something, I don't know what, was wrong about them. She was handsome a large, tall, sedate woman with dark hair and eyes. She was too good for him, as she was seemingly quite refined...

"He was continually beating and choking the woman. Ever since they moved in some time in December, he has been awfully cruel to her."

The News would later report:

Painter bore a bad reputation. He was ordinarily considered a "bum" and loafer who lived off the immoral traffic of the Martin woman. It was said he spent and gambled away the money she made as a woman of the town and that he frequently beat and choked her, and at times even threatened to kill her if she didn't supply his demand for money.

On the night of May 17, "as usual, he came in and immediately began quarreling with her," Truesdale said. "Suddenly my husband and I heard an awful noise, as though something were being dragged about and occasionally bumped against the wall, shaking the whole house. Suddenly a terrible shriek rent the air and we went to the head of the stairs and just then Mr. Painter came out of the front door, made a survey of his person and immediately returned. About two minutes later he came out of another door, and coming to the foot of the stairs, he called out: 'Any of you people up? Some one has killed Alice.' Then he rushed out of the door for a policeman. We were frightened and did not dare to go upstairs, for Alice had often told me Painter was dangerous."

According to other accounts, some fifteen minutes of silence passed before Painter went into the stairwell for the second time and yelled up at his neighbors, saying, "Good God! Are all you people dead? Somebody has murdered Alice. Come down quick."

The policeman and Painter hurried to his apartment. Inside the bedroom, they saw Alice Painter was stretched out on the floor, her face and neck looking like one mass of blood. The bed and almost every piece of furniture were spattered with blood.

As the body was taken to the morgue, the police took Painter under arrest. In the morning, he was brought to the officer of Inspector Hathway for questioning, with Captain Hayes and his lieutenants present.

"He was faultlessly dressed in a blue coat and vest, light trousers, dress shirt and light derby hat," the Daily News reported.

The police questioned Painter closely, but all he would say was that he had found Martin's body when he came home from a saloon at midnight.

The police were about to give up on the interrogation and send Painter back to his cell when Hayes noticed several large blotches of blood on Painter's light overcoat. Painter turned pale for a second and then regained his composure. The police examined the rest of his clothes, but found no other stains.

"How do you account for these blood stains?" Hayes said.

"I will do all that at the proper time," Painter said. "I was at Shiller's saloon, on Madison Street, within two blocks of Green, last night, and may have got something on my coat there."

"How late were you at the saloon?"

"Until they closed up."

"What time was that?"

"About 11:58."

"That gave you plenty of time to get home before 12:30, didn't it?"

Painter refused to say anything more.

Several detectives went to Painter's home to examine it for evidence. They found a flat of four elegantly furnished rooms with a handsome Brussels carpet and pretty chintz curtains.

The investigators couldn't find anything that appeared to be the murder weapon, but the pillows and bedclothes were soaked with blood and the head of the bed was streaked with gore. They believed the woman had been choked and her head had been battered against the bed post.

The stocking on Martin's left leg had been pulled down over the top of her show. "Woman of this class carry their money inside the stocking on the left leg and the state's theory was that Alice Martin's murderer knew where to look for it," the News reported.

During Painter's trial, his defense called on a number of alibi witnesses, who said Painter had been at the saloon until midnight or a few minutes earlier. And the defense argued that the neighbors' story indicated the murder had happened at midnight. Painter claimed he had walked the three and half blocks from the saloon to his home slowly that night, because he had rheumatism in one foot.

He said he had walked into the flat, finding the bedroom door closed. He said he made a slight noise to let his mistress know that he was home. He heard no response, so he sat down at the kitchen table, ate a sandwich and read a newspaper for a few minutes. He went again to the bedroom, knocked on the door. Still no response. He tried to open the door and discovered it was locked. He said he then pried it open with a stove hook and found Martin's lifeless body there, in the same state that police found it in a few minutes later.

Painter was found guilty of murder, and on June 22, 1892, he was sentenced to hang.

The case was appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court, which granted a stay of execution, but then upheld the conviction. Painter's case was only beginning to get interesting, however.

First, Painter asked to be hypnotized so that he could tell the truth about what happened on the night of Alice Martin's death. The courts refused to allow the hypnosis.

And then Painter's lawyers unearthed some new evidence, claiming that the killer was actually Dick Edwards, an old paramour of Alice Martin's who was serving time in a Texas penitentiary for another crime. The lawyers got affidavits from several witnesses who said they'd seen Edwards in Chicago on the night of Martin's murder, threatening her.

Governor John Peter Altgeld granted Painter a reprieve from execution while he studied these affidavits, but the new witnesses were considered to be people of "bad reputation."

Another witness came forward then, saying he had seen Edwards on the night of May 17, 1891, in a washroom at a West Side hotel. The witness said Edwards had had blood on his hands.

On the day before Painter was scheduled to be hanged, several of Chicago's prominent citizens signed a petition asking for another delay. A few hours before midnight, a telegram arrived from the governor, granting another reprieve.

Painter's three escapes from the gallows generated intense interest in the case. A Chicago medium claimed to have received a message from the murder victim, urging Painter's life to be spared because he was innocent.

Curiosity-seekers flocked to Painter's former home. An Italian family that lived in the building reenacted the crime for visitors, telling the story in broken English and pointing out blood spots.

At 7:45 A.M., about seventy-five spectators, city and county officials and reporters gathered in the jail's north corridor in front of the scaffold. Guards marched Painter into the room at 7:50, his arms pinioned behind him with a strap and his hands in manacles. He wore a small skull-cap, which he had been wearing regularly since his arrest, and he was smoking a cigar. He appeared to be calm and collected.

As the officials walked him onto the scaffold, Jailer William Morris took the cigar from Painter's lips and flung it away. He whispered to the condemned man that he could speak if he so desired. Painter began to speak in a low, trembling voice.

"Gentlemen, I see some friends here. Oh, God forgive a friend of mine who would come to see me die. It hurts me. Gentlemen, if you are gentlemen, there are few would like to look at an execution. There was a time in India when men sought death because it advanced them in a future state.

"I hate death. I don't want to die. I don't want to die. Listen to this. I swear this, if I killed Alice Martin, my life, although the courts have taken it away—"

Painter faltered, and the jailer whispered to him, and then he continued.

"I swear this. If I killed Alice Martin, the woman I loved, whom I would almost commit a crime for, I pray in this my last moment on earth that I be condemned to a flaming hell for all eternity. Listen! If there is a man here who is an American, on his soul I say to that man, see that the murderer of Alice Martin is found. Good-bye."

The jailer placed a strap around Painter's ankles and another around his thighs. A white gown was placed upon him, and then, looking over the crowd, Painter uttered his last words: "I see a hundred kind officials here but not one American."

A minister said a prayer. Some spectators rushed out of the room. Painter's skull-cap was removed and a white hood was pulled over his head, fastened at the neck with a draw string.

Jailer Morris took the noose, enlarging it slightly with his hands and placing it over Painter's head. He pulled the knot close up under Painter's left ear.

The officials stepped away from the trap door. Sheriff Gilbert gave the signal to a man concealed in a box, who used a mallet to strike a blow against a chisel, cutting the rope that held the trapdoor shut.

Painter's body shot downward. The trap door made a crashing sound as it swung back and struck the platform.

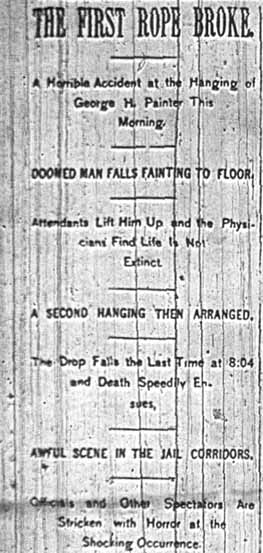

And then it seemed as if every man in the room gave out a half-suppressed gasp of horror.

The rope tied to Painter's neck had broken. His body fell to the floor in a heap.

As spectators looked at one another's stricken faces, the jailers rushed down to Painter's body and carried it back up to the platform. Several doctors came to inspect the body to determine whether Painter was dead, while the jailers hurriedly prepared another noose.

The doctors agreed that Painter's neck was broken, but they disagreed about whether he was dead.

One of the deputies cut the noose from Painter's neck. The white hood turned red as blood began to pour out of Painter's head.

The jailers carried the body by the leg straps and raised it into a sitting position on the trap door, as blood continued to run down Painter's body, now staining the white gown. Some spectators turned away from the sickening spectacle or ran out of the room.

When the jailers let go of Painter's body, it fell back into a reclining position.

After a few minutes, their yells and curses died off, and it was silent again.

The trap door was sprung again at 8:03, and the body plunged into the space underneath the scaffold, swinging in slow circles. The bloody gown opened in the back and fluttered loosely, showing Painter's manacled hands and his blood-soaked clothing.

The county physician stepped forward and held Painter's wrist until 8:07, when he declared him dead. Eight minutes later, Jailer Morris loosened the rope and the body was lowered to the floor.

The doctors who examined Painter's body believed the man had died before the second hanging.

Speaking to a reporter afterward, Morris appeared pale, sweaty and nervous.

"The rope was tested last night with a bag of sand weighing 200 pounds and I cannot account for its breaking," he said. "It is a piece of the same coil with which the anarchists were hanged and has been in the jail since 1887. Perhaps it became weak at some spot through age, but it stood the test all right last night."

"I feel that George is innocent of the crime charged against him," said Painter's brother, Jasper, who lived in the west suburb of Aurora, "and that an official murder has been committed."

© 2003 by Robert Loerzel.

Sources

Chicago Daily News, May 18, 1891; Jan. 26, 1894.