READ CHAPTER 1

GALLERY

WHO'S WHO

ATLAS

MYTHS DEBUNKED

FAMILY TREE

CONTACT THE AUTHOR

UPCOMING EVENTS

REVIEWS

CHICAGO HISTORY LINKS

READING SUGGESTIONS

BUY THIS BOOK

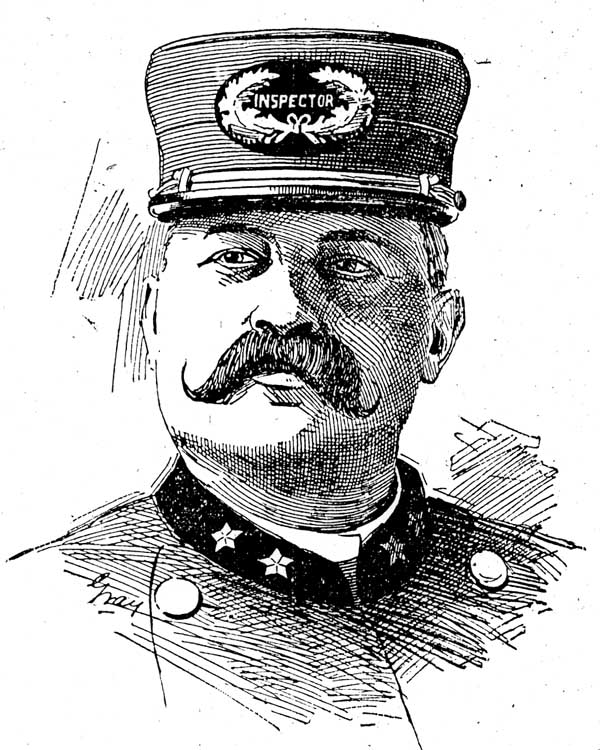

Michael John Schaack

Born: April 23, 1843, at

Saptfountaines, Luxembourg.

Parents: Christoph (an expert locksmith) and Margaret Schaack.

Moved: His family came to the

United States in 1853, and settled in Cairo, Illinois, in 1858.

1869: Joined Chicago Police Department.

1886: Leads the investigation of the Haymarket Square bombing.

1889: Publishes a book on the Haymarket Square case, Anarchy and

Anarchists. Read

excerpts. Around the same time, Schaack is dismissed from the police force,

facing charges that he had manufactured evidence.

Circa 1892: Schaack is reinstated with the police. A new office is

created for him: Inspector of the North Side.

April 30, 1897: After

Alderman Thomas O'Malley

is acquitted of murder,

some powerful figures in Chicago push for Schaack's dismissal, but mayor Carter

Harrison II refuses to take him off the force.

Read the Chicago Daily

News article.

May 1897: Schaack is involved in the investigation of Adolph Luetgert.

Address in 1897: 225 N. State Street.

Police rank: He was a captain at the time of the Haymarket case. At the

time of the Luetgert case, he was commonly referred to as "Inspector." According

to an obituary, he was commander of the Fourth Police Division.

Wife: Christina Klassen.

Children: Edward M., Charles W. and Margaret J.

Nephew: Philip Peiffer.

Died: May 18, 1898, after several weeks of illness. His condition was

diagnosed as diabetes with inflammatory rheumatism. A newspaper estimated the

value of his estate at $500,000. The Chicago Chronicle reported:

Immediately before his death he was sleeping peacefully and members of the household walked about on tiptoe lest they might disturb his rest. His physicians had said that if he survived the night his complete recovery might be expected... Inspector Schaack’s health had been poor since the conclusion of the famous Luetgert murder trial. To his incessant work on that case for several months may be attributed his death. The inspector spoke his last words shortly before noon yesterday. His son Edward asked him if there was anything he could do for him. "No, Edward," the inspector answered. "Oh, I’m not going to die yet."

Upon Schaack's death, the Chicago Tribune quoted Judge Joseph E. Gary saying: "He was one of the best police officers I ever knew. I tried the Anarchist case, in which he did excellent work. More recently the Luetgert case was before me, but Inspector Schaack always gave Captain Schuettler the great credit for that… He never colored his police work and put nothing in a case that was not properly there."

Captain Herman Schuettler said: "He was the greatest policeman the country has ever seen."

Of course, these quotes don't reflect the controversy and criticism Schaack had drawn throughout his career.

(Click on image below for a larger view.)

John J. Flinn's 1887 book History of the Chicago Police includes the following sketch of Schaack's career:

Michael John Schaack, whose management of the police end of the anarchist prosecution has given him a national reputation, was born in the Grand Duchy of Luxemburg, April 23, 1843, leaving the little frontier independency when thirteen years of age, after receiving a common school education.

His first dollar was earned in a furniture factory where he thought he was getting rich fast on three dollars a week. Next he worked in a brewery, and then sailed the lakes for seven years as second mate of various steamers hailing from Chicago. Several of the vessels were lost, but "the little cherub that sits up aloft looking after poor Jack," looked after him so well that he always managed to change ships just before the fatal voyage. After three more years spent in a brewery and two on Ludwig & Co.’s private detective force, he joined the police department, June 15, 1869, as patrolman, attached to the old Armory — that cradle of Chicago’s best officers, and served under Capt. Hickey.

He was not new to the rough side of police duty, when he was enrolled, having had some severe experiences when he was a "special." He had the good fortune, for instance, to reach Dewey & Co.’s place, at 27 Kingsbury street, on his rounds, just as their safe was blown out. There were four burglars inside, but he rushed in and was trying to see through the smoke, when one of the two men who had jumped out of the window, leaned in and fired at the intruder as the latter seized one of his comrades. A long dagger drawn by the burglar was met and matched with a heavy billy, but the revolver Schaack carried refused to explode. This man, Charles Johnson, and a comrade, were "sent up" for five years, the other two escaping. The next two desperate encounters were at Bogel’s store and Peterson’s tailor store on Kinzie and Kingsbury streets, in which shots were fired, but Schaack again proved to have a charmed life.

He was detailed for special detective work soon after his appointment, and was made a patrol sergeant in 1872, serving during Chief Washburn’s term. Then he was made a regular detective, and in the next five years had made 865 arrests in serious criminal cases, such as murders, burglaries, robberies and other penitentiary offenses. His partner in making this remarkable, and indeed unparalleled record, was Michael Whalen, now a detective.

After joining the regular force, one of the first feats which showed the qualities that were afterward to be so highly appreciated, was in a burglary case. While he was patrolling that beat Alderman Kehoe’s place, on North Clark street, was entered. This was bad for the man on the post unless he turned in the burglars, and Schaack felt worried, until one night he saw a suspicious-looking hack halt where the present Clark street viaduct is and turn into a dark alley, near a one-story jewelry store. He climbed up, leaned over the eaves, and listened. He heard one of the passengers instruct the driver to be ready to move off rapidly when they had the "stuff" in.

Schaack got down and watched. There was Alderman Kehoe’s cigars and liquor being loaded into the hack. Cautioning the driver not to move at his peril, he awaited the last trip out, and then grabbed the biggest burglar, who was much larger than his captor. The fellow fired two shots, and his partner threw Schaack to his knees. The big man then made for a marble yard, and the half-stunned officer after him. The pursuer hurt himself seriously by striking a marble block in the road and then stuck fast in the fence, when the burglar fired at him. But the case was taken up by Officer Dolan, and Charles McCarthy captured. He was an old freight robber, and he and his partner have the railroad company some valuable information, and escaped, at the intercession of the corporation, with one year at Joliet.

The capture of Tommy Ellis, who killed David O’Neil, the yardmaster of the Northwestern road, on the Erie street bridge, in 1877, was a desperate adventure. The murderer had to be shot twice before he consented to be arrested.

The capture of the leaders of the Murphy gang, while robbing Kobletz’s merchant tailor store, on Clark street, was another daring piece of police work. James Strong and George Harris were sent up for five years.

In August 1879, he was made a lieutenant, and attached to the Chicago avenue station. He was transferred to the Armory for awhile, but soon returned to the North Side again. While in the levee district he was shot at twice, but his wonderful luck or Providence preserved him. On one occasion, while arresting a gang of roughs on Pacific avenue, a bullet passed through his clothes, close to his abdomen, and then entered the trousers’ pocket of his partner, but harmed neither. A falling out with the Armory justice [Foote] led to his transfer back to Chicago avenue. The magistrate excited the zealous officer’s ire by certain rather extraordinary decisions, and received the benefit of a free and forcible expression of opinion upon his conduct in open court.

In August, 1885, he was made a captain, and two days afterward Mulkowsky murdered Mrs. Kledzic. This case is one of the most remarkable in the criminal annals of Chicago and created a sensation over the whole country. But the manner in which it was worked up was only less remarkable.

Mulkowsky had come over here from Poland after serving the twenty-two years, which constituted a "life sentence" there for murder, and which is scarcely ever survived. He came to Chicago under the name of Brunofski, and was not recognized by the Kledzic family, whom he had known before his crime and imprisonment. He remembered them, and now cultivated their acquaintance. He learned of some savings they had invested and the shape of the vouchers therefor. Coming behind the wife while she was alone in the house and bending over a wash-tub, he crushed her skull with some heavy weapon, ransacked the rooms, ravished her finger of its wedding ring and fled.

Capt. Schaack first got a complete history of his family and friends at home and here from Kledzic, who incidentally referred to Mulkowsky’s supposed fate in prison, and also mentioned Brunofski, whom he suspected of being other than he represented himself. In three days Capt. Schaack had the murderer in custody and circumstantial evidence upon which to hang him. Some burnt paper in the stove of the murdered woman’s room gave the first clue. It was the remains of letters relating to the release of Mulkowsky. From a sister of the latter, whom he much resembled, Schaack learned of the identity of Mulkowsky and Burnofski, and by means of photographs of the sister he was arrested. The watch of the murdered woman and her jewelry were traced to the prisoner, who was also found to have washed his clothes in the river at midnight and his hat was stained with what Dr. Bisfeldt swore was human blood. This completed the chain, and the jury was out only twenty minutes before convicting him.

Capt. Schaack’s crowning exploit, the conviction of the anarchists, is too fresh in the public mind to need any extended reference here. It is enough to say that, taking up a case which was out of his own district and conducting the investigation independently of any aid or suggestion from his superiors, he found clews of which no one else suspected the existence, and following them with a seal and intelligence that almost surpass credence, he forged a chain link by link, that completely encircled the conspirators.

The Krug case, of more recent date, was remarkable for the fact that the prisoner was convicted and is now in Joliet, serving what will doubtless prove a life sentence, after the coroner had once released him on the testimony of the county physician that the fellow’s last victim died, not by poison, but well-defined natural causes.

Pictures: Chicago Tribune, May 19, 1898; Chicago Daily News, 1897; Chicago Record, Sept. 13, 1897.