READ CHAPTER 1

GALLERY

WHO'S WHO

ATLAS

MYTHS DEBUNKED

FAMILY TREE

CONTACT THE AUTHOR

UPCOMING EVENTS

REVIEWS

CHICAGO HISTORY LINKS

READING SUGGESTIONS

BUY THIS BOOK

Born: May 4, 1863, Edwardsville, Illinois.

His father was a Latin professor at McKendree College; his grandfather

was Methodist minister; and his great-grandfather was a territorial legislator

who opposed slavery.

Childhood: He spent his early youth in St. Clair County, Illinois, and was

educated in the Lebanon, Illinois, public schools.

Education: Graduated in classics course at McKendree College in

1882; received a law degree in 1885.

Moved to Chicago after college.

Marriage: 1891, to Bina Day Maloney of Mount Carroll.

Political offices: Served as a state representative, attorney for the

sanitary board, and a member of the Republican state central committee. In 1896,

he was elected Cook County state’s attorney; he served two terms. He was

governor of Illinois for two terms, serving from 1905 to 1913. He was elected to

U.S. Senate in 1924 and served for one term.

Died: February 5, 1940, in Chicago; was still practicing law at the time.

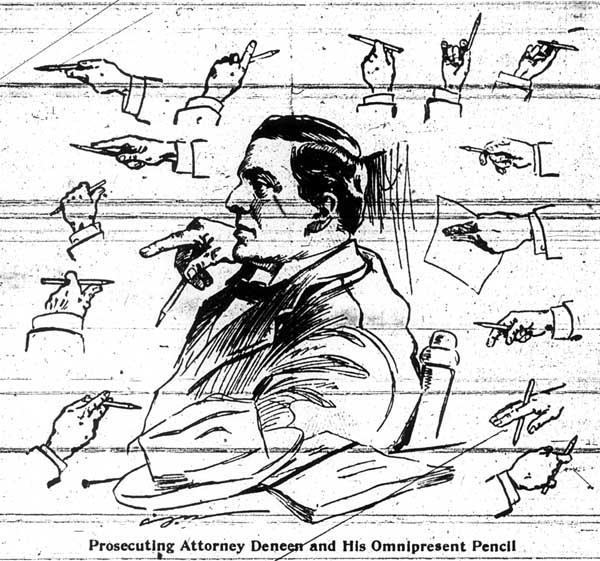

A caricature of Deneen from the Feb. 13, 1898, Chicago Chronicle (the cartoon alludes to indicted banker Edward Dreyer).

In the book Mostly Good and Competent Men: Illinois Governors, 1818-1988, Robert P. Howard writes: "A cold and cautious man, Deneen didn’t know how to engage in political small talk with the Democrats and conservative Republicans who made his leadership difficult. Effective, unpopular, and durable, Deneen could, nevertheless, count considerable accomplishments. His honesty was never questioned, and the 'jackpotters' who sold their votes in the legislature detested him." Howard describes him as "a short and stocky man with a look of bulldog determination on his face."

On January 2, 1898, the Chicago Times-Herald published the following review of Deneen’s first year in office:

His honesty is unquestioned. The office of state’s attorney and all its machinery are to-day regarded with suspicion and distrust by every gambler, every thief, every blackleg attorney, every corrupt politician in the city of Chicago. That they are no longer habitues of the corridors leading to it, no more welcome guests in the private chambers, may be taken as evidence that their suspicions are justified that the office is operated on different lines than it was in one or two former regimes. …Grand juries are no longer used for the purpose of blackmailing merchants or criminals…

[His family had come to Illinois] because abolition sentiment was strong here. They fought against … slavery in the civil outbreak. They were the kind of people that owned slaves in the south, and when they reached the north freed them. One of them was indicted in Georgia for daring to say that a negro and a white man probably would reach the gates of heaven at the same time…

Here in Illinois, at Troy, they burned in effigy a Deneen who spoke against slavery. He continued speaking. He was of the stock that carried the Bible in one hand and a rifle in the other …

He and Mr. McEwen arrived in Chicago on the same day in 1885 and met in the same office that day — Judge Booth’s — and afterward were clerks for E.W. Russell. Later they were law partners…

He is not a man given to protesting his honesty… He is very much given to minding his own business…

[In a speech a year earlier Deneen had said:] "The office shall not be a collection agency for chattel mortgage concerns, money loaners or usurers, nor shall it be a pawnbroking establishment, a second-hand store or a fence. The indicted man against whom there is sufficient evidence to warrant a belief in his guilt, according to the law, will be tried no matter what his social position, religion, politics or color… The state’s attorney’s office will not be used as a cloak to ennoble dishonest grand juries to blackmail citizens or criminals. By the natural bent of my mind the criminal with influence and friends will be prosecuted with greater vigor than the one who is penniless and friendless…"

At the time Thomas J. O’Malley was indicted strong influences were exerted to prevent trial. O’Malley was beloved by a host of people, and a strong public feeling existed that he was a victim of persecution. But a grand jury had found indictments against him and Santry, and those indictments had been secured by an assistant state'’ attorney, for whom Mr. Deneen was responsible. The latter was sick in bed. He had hardly been in office a week. One long cry went to him to avoid trial. He got out of his bed, came to his office, insisted on trial, presented the law and evidence in all the prosecution for nearly fifty days, and at the end of that time, the accused being declared innocent, could be conscious that the very man he had tried respected and honored him. O’Malley said so, and told him so to his face…

Pictures: Chicago Tribune, Aug. 23, 1897; cartoon, Chicago Chronicle, Feb. 13, 1898; Deneen and His Omnipresent Pencil, Chicago Journal, Sept. 23, 1897; Deneen's first year in office, Chicago Times-Herald, Oct. 11, 1897.