READ CHAPTER 1

GALLERY

WHO'S WHO

ATLAS

MYTHS DEBUNKED

FAMILY TREE

CONTACT THE AUTHOR

UPCOMING EVENTS

REVIEWS

CHICAGO HISTORY LINKS

READING SUGGESTIONS

BUY THIS BOOK

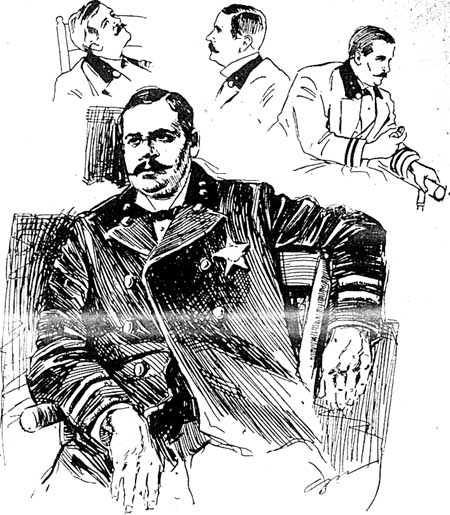

Herman F. Schuettler

Born: July 14, 1861, in a house at Cleveland Avenue and Blackhawk Street

in Chicago.

First job: Schuettler worked as a conductor on the Larrabee Street horse

car line.

June 13, 1882: Schuettler becomes a Chicago police patrolman, working in

his home neighborhood.

Married: 1884, to Miss Katherine J. Flint of Watertown, Wisconsin.

1886: Transferred to the Central station.

1888: Working on Michael Schaack's squad of anarchist-busting policemen,

Schuettler makes a daring arrest of Louis Lingg.

1888: Schuettler becomes a patrol sergeant in the old Harrison Street

police station. Later the same year, he is promoted to lieutenant.

1889: Schuettler is a key player in the solving of Dr. Patrick Henry

Cronin's murder.

January 21, 1890: Appointed captain and assigned to the Sheffield Avenue

police station.

January 29, 1890: Confronted by three Irish-Americans with the

Market Street

Crowd angry over the Cronin case, Schuettler gets into a scuffle and fires

his gun, killing one of the men, Bob Gibbons. Schuettler is acquitted of murder

after his lawyers argue he shot Gibbons in self-defense.

1897: Schuettler is a lead investigator in the Luetgert case.

Home address in 1897: 810 Bosworth Avenue.

1900: Travels to Europe to study police departments there.

1903-08: Schuettler heads up a "flying squadron" that cracks down on

gambling establishments such as

poolrooms

around the city. The crackdown displeases some of Chicago's politicians.

1904: Appointed assistant chief of police.

1908: Police Superintendent George Shippy kills an immigrant laborer,

Lazarus or Jeremiah Averbuch, who had come to his home. Shippy claims

self-defense, saying that Averbuch had tried to assassinate him. Schuettler

heads up the investigation. Although there is no evidence that Averbuch was an

anarchist, Schuettler leads a roundup of suspected anarchists in Chicago. He

also thwarts the plans of Emma Goldman to speak during a visit to the city. This

story is recounted in the well-documented and thoughtful book

An Accidental

Anarchist by Walter Roth and Joe Kraus.

1913: His title is changed to first deputy superintendent.

January 11, 1917: Appointed police superintendent.

Fall 1917: Schuettler suffers a "nervous breakdown."

Jan. 20, 1918: Schuettler goes to Florida, hoping to recover.

Late May 1918: Returns to Chicago, then suffers a relapse.

Died: August 22, 1918.

Children: Mrs. Edgar Nelson, Mrs. Frank O. White and Dr. Arthur

Schuettler.

Schuettler's early career

John J. Flinn's 1887 book History of the Chicago Police includes the following sketch of Schuettler's career:

HERMAN SCHUETTLER is one of the young men of the detective force, having been born in Chicago in 1861. In addition to being about the youngest man on the force, he is the tallest.

He was appointed to the force June 8, 1883, and was only kept in uniform a short time. So clever an officer was more valuable in citizen’s clothes. In connection with Detective Officer Stift, Officer Schuettler worked up the case of Lorenz Krug, who was charged with poisoning Lucy Heidelmeyer, and Krug was convicted. It was the first conviction in a poisoning case ever secured in Cook County.

Klein and Tiedeman, the highwaymen, were brought up with a sharp turn by this young officer, and treated to eight years each in the penitentiary.

William Heller, an expert burglar, who had gone through most of the fine residences in Lake View, was run down, and sent to Joliet for three years. Over fifty cases were developed against him after he had gone down, and when he was released, in the summer of 1887, he was rearrested and given twenty years.

Officer Schuettler was a valuable aid to Captain Schaack in the working up of the Kledzic murder mystery, for which Mulkowsky was arrested and hanged.

But his widest reputation was gained during the anarchist troubles. He it was who tracked Lingg, the bomb-maker, to his hiding place on the South Side, and there bearded him in his den. Lingg made a desperate resistance, trying his utmost to kill the officer with a knife or revolver; but Schuettler, being young and strong as an ox, overpowered him by main strength, and made him a prisoner.

(Click on the image below for a larger view.)

On November 2, 1913, the Chicago Tribune published a story about the Luetgert case. In response to the question in the headline, "Murder — Will It Always Out?" Schuettler, who was then first deputy superintendent of police responded:

"It depends… It depends on the police and the investigators working on the case. It is true that the murderer always leaves some clew, but that clew must be found before the mystery can be unraveled. When Adolph L. Luetgert, the sausage maker, put his wife in 500 pounds of dissolved potash he figured that the corpus delicti would be entirely destroyed. Luetgert had a fairly good understanding of the law, and he knew that without a corpus delicti no case could be proven. He had read up on chemistry, too, but he had not learned that potash would only destroy animal matter and not destroy mineral matter. In this instance, too, failure to report the case aroused suspicion in my mind. It seemed strange to me that Luetgert, who had a short time previously insisted on a vigilant search for two Great Dane dogs, should fail to report the disappearance of his wife."

Ben Hecht Describes Schuettler

In his 1963 book Gaily, Gaily, former Chicago reporter Ben Hecht describes encountering Schuettler sometime during the 1910s:

I move on to the office of Assistant Superintendent of Chicago's Police, Herman Scheuttler [sic], called "Wooden Shoes" by his admirers. I was interviewing him about the derisive post card he had received from the hunted bandit...

I pause in my story to tell a bit of Chief Scheuttler, who looms like a hundred melodramas in my memory. Chief Scheuttler was a law enforcer as unbelievable as any to be seen on our television screen today. He was a tall, bulky, implacable enemy of crime, honest as the day and courageous as the lion. In his youth, as a police lieutenant, Scheuttler had made a spectacular capture of the anarchist Louis Lingg, leader of the Haymarket Riot's bomb throwers...

That was many years ago, but it was the same stalwart crime-hater who spoke out of his chief's chair about Teddy Shedd.

"I'm going to get Teddy Shedd," Chief Scheuttler said, "and I promise you this. That murdering little squirt will go to trial with a broken jaw and an ear missing. I'm going to take the little bastard apart before I bring him in. You can quote me for that, and I don't care if it costs me my job. He killed two policemen."

Schuettler's Death

The Chicago Tribune published the following obituary for Schuettler on August 23, 1918:

Chief of Police Herman F. Schuettler is dead. The veteran of Chicago's police force died at the Alexian Brothers' hospital at 8:20 o'clock last night.

His death was not unexpected. He had been ill for months and early yesterday morning his family knew the end was near. They were at his bedside when he died.

He died while apparently in a peaceful sleep. He had not spoken for hours, but until he lapsed into the last sleep he had been fully conscious.

The courage that made Herman Schuettler the most romantic figure in the police history of Chicago remained with him till the end. His last act was to shake the hands of members of his family in a last farewell.

His wife, Mrs. Katherine Schuettler, had been with him constantly. Yesterday morning his daughters, Mrs. Edgar Nelson and Mrs. Frank O. White, were summoned to his bedside. Later his son and daughter-in-law, Dr. and Mrs. Arthur Schuettler, arrived.

At 7:20 last night Acting Chief John Alcock and Charles Agnew, the latter Chief Schuettler's secretary for twenty years, arrived at the hospital, called from a meeting of the city council by a telephone message that the big man of the Chicago police department was dying.

The family was grouped about the bedside when Acting Chief Alcock entered. Raised slightly by his pillows the dying chief espied the tall figure of the acting chief over the heads of the sorrowing group about the bed. He nodded and smiled and held out his hand.

He clung to the hand of the acting chief for nearly five minutes. Then, with characteristic courage, he took the hand of Charles Agnew and then of the members of his family. He said no word. Then he went to sleep. A few minutes later he was pronounced dead.

Some hours later a group of hospital attendants passed through the corridor of the hospital with a wicker basket bearing the last remains of a man whose courage and ability pushed him up through the ranks to become and be hailed as the greatest police chief Chicago ever had.

A group of police officers and newspaper men stood by with heads bared.

Mrs. Schuettler was prostrated by the shock of her husband's death...

About 8:30 o'clock a touring car drove up before the North Halsted street station and Acting Chief Alcock alighted and hurried up the steps. He asked the desk sergeant for a police wire and called Sergt. James Walsh, in charge of the switchboard at the detective bureau, telling him to announce that the chief was dead.

So the word went out of the passing of "Old Herman." Every station was called, the captains, the lieutenants, even the patrolmen as they rang from the street boxes received the news:

"The chief is dead!"

The word was flashed to the fire alarm office and the words were clicked out over the fire alarm telegraph:

"Attention! Fire Department!"

Every fireman on duty, the chiefs and battalion chiefs in their homes, listened for those words mean always the announcement of import.

"Chief of Police Schuettler is dead!"

It was taken up and sent throughout the city.

The news of the death of the veteran detective and widely known police chief spread rapidly throughout the city. It was everywhere greeted with sorrow.

The city council was in session. Resolutions were quickly drawn and passed expressing regret and declaring that Chicago had suffered a sever loss. Tributes to the honesty, loyalty, courage, and ability of Herman Schuettler, who was liked and respected by officials and admired even by crooks because of his fairness and fearlessness, were heard everywhere.

The news was received with sorrow, but not with surprise, for Chief Schuettler had several times been reported as dying and it was generally believed that he could not live.

He first suffered a nervous breakdown last fall. On Jan. 20 he went to Florida, hoping to regain his health. He returned in late May, apparently improved, but a few days after his arrival he suffered a relapse. Several times during the summer he was reported as dying.

Always the great courage of the man pulled him through. At times it was even hoped that the strength of his giant frame and rugged constitution might save him. Pneumonia and other complications developed, however, and his giant's strength gave way. Wednesday night his fever went to 103 and those close to him realized that the end was coming to the man who was for years held up as a model to every rookie police officer in Chicago.

"He was the greatest of policemen," was Acting Chief Alcock's tribute, as he sat in the corridor of the hospital waiting for the body of his former chief to be brought down. "His last orders to me when he left for Florida were that the entire police department should be used in every possible way to assist the United States government in all its war work.

"His death is a distinct loss not only to this community but to the entire country. He was a patriot of the truest type.

"His integrity and honesty as a public official were never assailed. No one will deplore his death more than the policeman himself, from the high official to the man on the beat."

Mayor Thompson paid him the following tribute:

"Herman F. Schuettler left behind him as priceless heritage a name untainted and a record of achievement that time will not dim. Whatever the future may bring forth, the past has not seen his equal in police circles in this country. His fame was not municipal, but national, even international."

Chief Schuettler's exploits formed the basis of many a nickel thriller, but he was farm from spectacular in his method of operation. Rather he worked quietly and systematically.

Physically he approached the gigantic, towering above the biggest and most powerful of his subordinates. Temperamentally he was as kindly and thoughtful as a woman. He was born in Chicago, spent his whole life in the city, and knew its every alley.

He was born July 14, 1861, in a house that stood at Cleveland avenue and Blackhawk street. And it was in this north side district he performed most of his notable work. His first job was that of conductor on the old Larrabee street horse car line. On June 13, 1882, he joined the police department, traveling a beat in his home bailiwick.

His natural sagacity and his great strength gained him instant recognition, and the unruly characters of that day and place found much reason to shun his heavy fist. He was attached to the Chicago avenue station for a short time and then transferred to the Central station in 1886, where, by appointment of Chief Joseph Ebersold, he became a member of the famed anarchist squad.

Louis Lingg was one of the anarchist leaders and a bad actor. He was the maker of the bombs used in the Haymarket riot of 1888. Schuettler set out to take him. He found Lingg in a house that stood at 80 Ambrose street and the anarchist flew at him with a revolver. In the struggle that followed Schuettler bit off one of Lingg's fingers to save himself from being shot.

In 1888 Schuettler became a patrol sergeant in the old Harrison street station and in the same year was promoted to lieutenant. On Jan. 21, 1890, he became a captain and was assigned to the Sheffield avenue station.

It was in 1889 he did much to solve the murder of Dr. Patrick Henry Cronin, one of the epochal events of the police department.

Cronin's body was found in a catch basin at what now is Foster avenue and Broadway. It was then a far removed suburb. Patrick O'Sullivan and Martin Bourk were sentenced for life. Dan Coughlin, a city detective, was tried twice; once convicted and then acquitted.

The murder of Mrs. Louise Luetgert, wife of a northwest side sausage maker who was convicted of disposing of her body in a lime vat, brought Schuettler into more prominence...

In 1900 Schuettler went abroad and studied police conditions in continental cities, bringing many features into the Chicago department. In 1903 he forced a confession from Gustave Marx, one of the car barn bandits, which resulted in the capture of all four.

In 1904 Schuettler became assistant chief of police, retaining that position through all the vicissitudes of political storm and charges of graft which have racked the department. In 1913 his title was changed to first deputy superintendent.

Chiefly notable is the fact that through his whole career there never was suggested the smallest hint of dishonesty, an item most noteworthy in connection with a business that has caused the downfall of many men. He was said to have entertained but one great ambition —to be chief of police in Chicago and close his public career in that position. He had been offered the post numerous times, but always refused, considering the term too short and himself too young to think of retiring. When finally he accepted the office it was with the understanding he would close his police work when he relinquished the baton of chief.

That he "died in the harness" was said to be his greatest wish achieved.

Schuettler was married in 1884 to Miss Katherine J. Flint of Watertown, Wis. There are three children: Mrs. Edgar Nelson, Mrs. Frank O. White and Dr. Arthur Schuettler.

Pictures: first image, source uncertain; Chicago Journal, Sept. 3, 1897; Chicago Record, Sept. 13, 1897.

Seach the Library of Congress site for

Chicago Daily News photos of Herman Schuettler.